“Easy as ABC” – Approaching the ‘Modern Sound’ in UNESCO Radio

“The control and regulation of sound, especially the sound of the human voice, is of essential importance to the fundamental operations of the Headquarters of the United Nations.”1

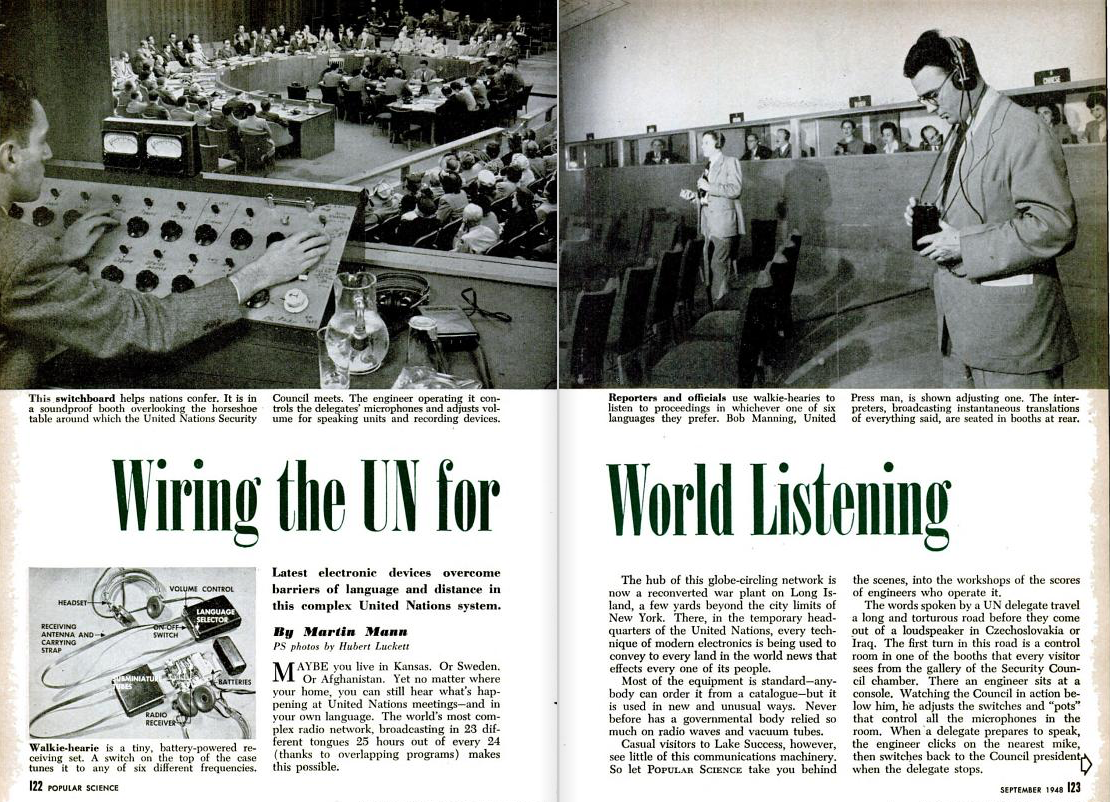

The planners of the United Nations (UN) were acutely concerned with how the new international organization would sound. In order to “strive for the highest possible value of speech intelligibility,”2 the Permanent Headquarters’ acoustically contoured assembly chambers and conference rooms were outfitted with state-of-the-art “sound-absorbing materials” intended to limit the reverberation time resulting from carefully placed microphones and amplifier arrays.3 This expertly designed4 “sonic assemblage”5 of techniques employed within the Headquarters extended to an outward-facing practice with the organization’s radio broadcasts to “the peoples of the world.”6

As evidenced by the digitized contents of the UN Audiovisual Library, the first decades of the organization saw its multilingual production of numerous feature programs and informational bulletins that targeted an (ostensibly) international listening audience. Existing scholarly work addressing UN Radio examines its role during the peacemaking process,8 though there is apparently little to no existing work that directly analyzes this sound archive. This is a notable lacuna, especially given the extent to which the UN’s radio broadcasting project was conceived as a cornerstone of the organization’s informational mandate.9

Sonic historians have demonstrated that there is much to gain towards our understanding of the past by foregrounding meaningful sonic dynamics.10 Following such contributions to international and diplomatic history,11 the UN’s web-accessible radio broadcast archive can be approached as a collection of historical aural/oral performances that carry empirical significance. These materials can be approached as historical “sonic formations” that were productive of “political dynamics” through their meaningful ordering of sounds.12 In what follows, I sketch out a means of interpreting the historical sounds of UN Radio using digital audio analysis and reference to relevant textual records to aid a “close listening”13 approach to one of the archival recordings.

Easy as ABC

In the late 1950s, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) collaborated with UN Radio to produce “[a] series of 20 half-hour programmes”14 titled “Easy As ABC”15––described as an “educational series for children.”16 Each of its alphabetically themed entries featured a star-studded cast of Hollywood actors and popular singers who voluntarily performed scripted featurettes that accounted the organization’s activities, successes, and aspirations. I focus here on the second installment, “B is for Bargains” (1958),”17 which highlights UNESCO’s deployment of “experts” and “specialists”18 in the “Technical Assistance” of the world’s “under-developed regions.”19 This programme surveys such varied efforts as the establishment of a radio station in Tehran with the help of “one expert from France,” laboratory equipment and training for natural resource exploration in Pakistan set up by “[o]ne British technician sent by Unesco, ” and a “Cosmic Ray Laboratory on a mountain top in Brazil, developed with the help of Unesco experts.”20 “B is for Bargains” also showcases UNESCO’s Arid Zone Program, which endeavored (to negligible results)21 “to make more dry land agriculturally productive as well as to prevent what was believed to be the spread of deserts.”22 As its title suggests, the radio programme frames these development-oriented projects as inexpensive bargains for the organization’s member states by emphasizing the impactful results won by the efforts of a few tactically distributed experts.

After a preamble that establishes the series’ lighthearted tone with a full-length theme song in a swing jazz style, narrators ‘Alpha’ and ‘Beta’ invite Hollywood actors Myrna Loy, Dinah Shore, and Edward G. Robinson to help explain “why B is for BARGAINS.”23 They approach this hook by playing four short “recordings” of the sounds of women “hunting for a bargain”24 during “bargain days” in four Western metropoles (Paris, Rome, London, and New York).25 With the exception of Rome, these are all locations where this radio series was produced.26 Probably best characterized as scripted skits with added background recordings, each of these short interspersions presents an auditory vignette that transports the listener to a starkly different soundscape from the relatively unadorned, “dead”27 sonic character of the radio studio: instead, a loud panoply of sounds characterizes all of these audio-visits.

I strongly encourage the reader to listen to this section––it begins at 8:00 minutes in the archived recording. Despite their respective geographic distance and the different languages heard, these sonic depictions of department stores in the four cities are very similar in terms of sonic presentation. We hear shoppers’ hurriedly anxious and/or raised voices accompanied by loud sounds––including mechanical noises, sounds of bustling crowds, coughing, intermittent squeaks, wailing babies, department store background music, bells, and reverberant echoes––in hectic auditory scenes conveying consumer fervor over temporarily reduced prices. Following R. Murray Schafer’s helpful acoustic ecology terminology, these are great examples of “lo-fi soundscapes,” where “individual acoustic signals are obscured in an overdense population of sounds.”28 In the last excerpt, from “a city in the USA” (the script specifies “NYC”),29 two women jostle over a particular commodity with increasing intensity––culminating in a violent aural cacophony of smashing glass, screaming, paper ripping, and what sounds like a gunshot––before the skit fades out to silence.

Back in the studio after a beat, our narrators use these snippets to recall the gender-stereotypical notion that women (like Loy and Shore) know a bargain when they see one.

With this innate know-how invoked, the narrators start a “demonstration in Bargains and Merchandise” where they play another set of “recordings and sound effects”31 before explaining each in turn. This sound-identification game directs the listener’s engaged attention32 to the explanation for a non-specialist, potentially skeptical public33 that UNESCO’s transnational deployments of experts have been cost-effective. The productivity of UNESCO initiatives is presented as something that can be simply heard by listening to the new sounds that have been introduced by the organization in places where there were previously none, leaving local soundscapes around the world positively transformed in the wake of (often Western) technical expertise. In one passage, Robinson characterizes UNESCO’s Arid Zone Program as “a scientific battle to stop the deserts from growing larger, to make this sound heard everywhere,”34 as a recording of rain and thunder fades in behind his voice.

From the first of these sound-examples, which represents the Brazilian “Cosmic Ray Laboratory”35 built with UNESCO assistance––a verbally unacknowledged but audible and measurable sonic juxtaposition takes place. This audio clip centers a steadily whirring machine sound, accompanied by a droning motor analogous to the sound of a forklift. While this sound could be labeled “industrial noise,”36 its aural representation is markedly more restrained than the bargain day recordings. Compared to those stereotypical depictions of aural disorder, most of these ‘UNESCO-sounds’ exhibit acute signal clarity. Portraying among other activities the spraying of DDT to prevent malaria and a diamond saw employed in Pakistan’s fossil fuel exploration, these recordings are accordingly closer in sonic character to what Schafer terms “hi-fidelity” soundscapes, where the identities and locations of sounds are more distinguishable in the relative absence of excess background noise.37 Most intriguingly, these sounds depicting UNESCO’s assistance are some of the quietest signals within the constructed soundworld of this broadcast. Evidence of this observable intention to portray the organization in ‘quiet’ terms is also found in the programme script, where Robinson is given the reading direction “(SLOWLY – VERY QUIET AND MEANINGFULLY)” for his solemn reading of the initial lines of the UN Charter.38

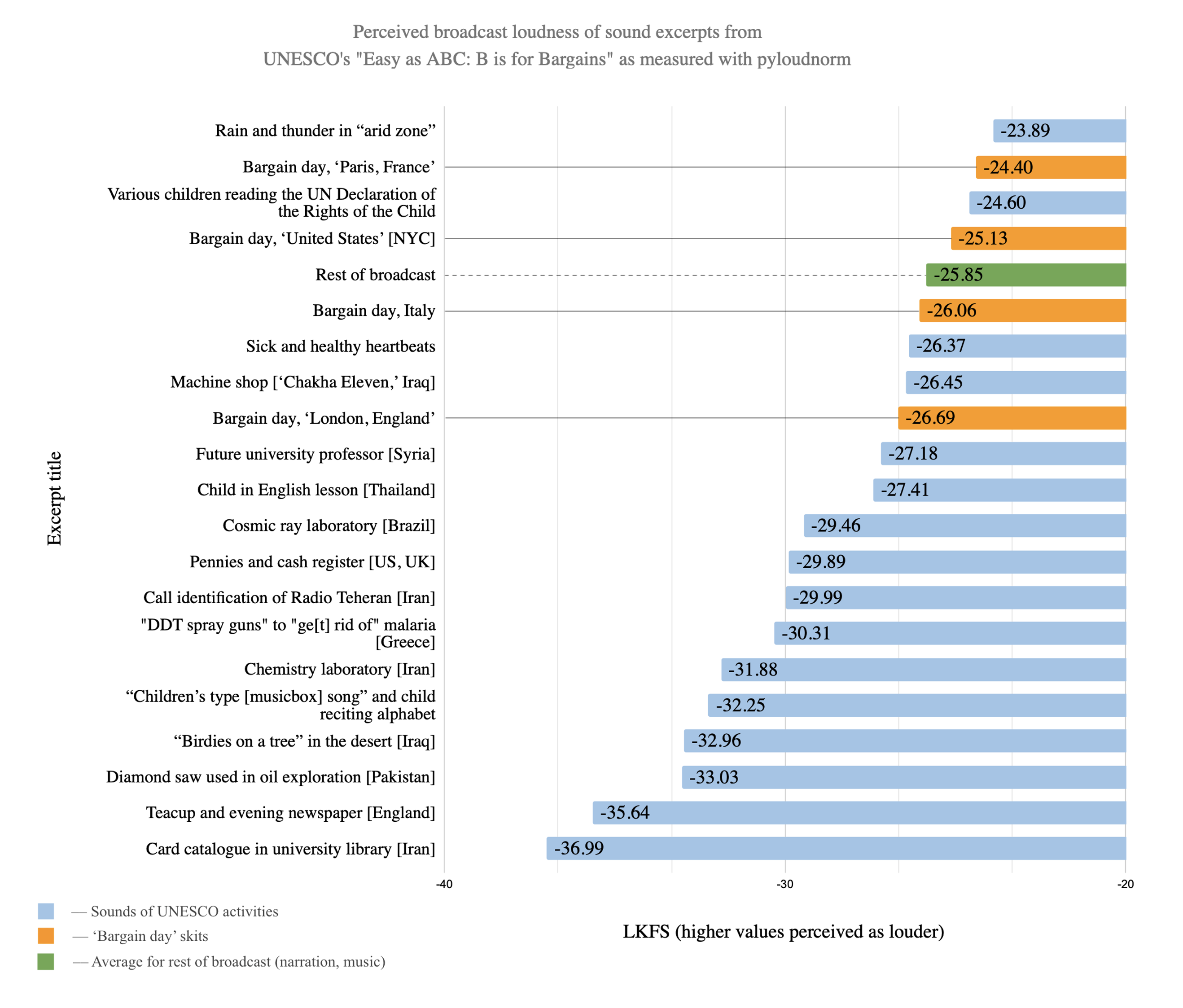

This aural positioning of UNESCO’s work as ‘quiet’ is measurable using digital techniques. To isolate each of the ‘bargain day’ recordings and the ‘UNESCO-sounds’ for measurement, I manually spliced them from the archived MP3 file and exported them (along with the remainder of the broadcast) with descriptive titles using the digital audio workstation Ableton 10. I then used ‘pyloudnorm,’ a Python package that facilitates the “ITU-R BS.1770 recommendation for measuring the perceived loudness of audio signals”39 to measure each excerpt. This technique employs a mathematical algorithm that applies frequency filters and gating techniques to sound files that “mimic the response of the head” and “reduce the influence of low frequencies” to account for human perception before calculating LKFS, a unit of loudness perception.40 This tool has at least two benefits for sonic history researchers. First, it is straightforward to use, and it runs on only a few lines of code. Second, and quite appropriate for this purpose, the signal processing algorithm that pyloudnorm automates is a standard set by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for “determining subjective programme loudness” of “broadcast content” within the “[r]adiocommunication sector.”41 I configured pyloudnorm to simply report an LKFS measurement for each of the excerpts that I extracted from the broadcast:

The result of this exercise is a measurement of the audible distinction between each of the sets of non-narrational sounds that give the programme its structure: the ‘bargain day’ sounds and the sounds of UNESCO’s development activities. With some exceptions, most of the sounds (in blue) that represent UNESCO are (and conceivably were) perceived as relatively quieter than both the ‘bargain day’ recordings and the rest of the broadcast (the latter encompassing, in the main, the broadcast’s spoken narration). This use of a digital analysis technique accordingly helps me to identify the presence of a meaningful distinction conveyed not through the spoken language of the broadcast, but via the sonic register. Such methods can help us begin to parse not only the intentional ordering of sounds by radio producers but also the historical conditions of listening, especially given we have an archived recording that preserves these subtle yet meaningful differences in measurable perceived loudness. The relative perceived loudness of respective features of this historical soundworld distinguish some examples of UNESCO’s work as quiet, as juxtaposed against scenes of the audibly louder, gendered dis-order of modern urban life, narratively located in four apparently prototypical Western cities.

The modern sound

This is a brief example of the type of analysis that can be done here, albeit one which raises more questions than it answers––for example why is this relative quietude and sonic isolation the sound signature associated with many of the references to UNESCO’s work in this radio programme? This observation can be linked to what Emily Thompson has dubbed the “modern sound,” a set of principles that concretized with the increased use of (electro)acoustics technologies during the early decades of the twentieth century.42 This “modern sound” is encapsulated by the preference for the removal of unwanted “noise”––encompassing both the “outside noise” of the postindustrial city and the internal reverberations of architectural space––using “soundproof[ing]” techniques refined by “architectural acoustics” practitioners.43

The ‘modern sound’ thus favors those signals that are “clear and direct.”45 The UN Headquarters’ planning documentation reflects this standard well: for example, the Secretary-General’s 1947 report notes that “acoustic treatment [in the Headquarter’s planned broadcasting studios] will be considerable since they must be very ‘dead’”46––meaning they exhibit the total dampening of undesirable room echo. Thompson argues that the modern sonic ideal “signaled the power of human ingenuity over the physical environment” through its upholding of a ‘pure’ sound signature facilitated by advancements in science and technology, and the historically contingent accumulation of expertise and best practices.47 The UN’s sustained use of these techniques of noise-limitation and signal clarity––across its architecture, audio circulation technologies, and indeed within its radio broadcasts––accordingly parallels the international organization’s comprehensive championing of scientific expertise across all areas of its administration, a tendency of that Jens Steffek has described as “technocratic-utopian.”48 All of the sounds of UNESCO’s work depicted in “B is for Bargains” exemplify the modern sound through their discreteness: each depicts one or two clearly identifiable, hi-fi sound sources not masked by spatial echoes or environmental sounds. In a recording of birdsong that is supposed to represent new “trees in the [Iraq] desert” grown following the initiative of “one expert from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Agency,”49 we don’t hear much of anything but a dry, close-mic recording of birds. With all the sound-mixing facilities of the radio studio, capable of concocting such sonic flurries as in the ‘bargain day’ recordings, a richly choreographed and complex soundscape was certainly possible. However, this was eschewed for the ‘UNESCO-sounds’ in this episode.

The ‘modern sound’ helps to contextualize UN Radio’s decision in this case to revert to austere and subdued presentation when showcasing UNESCO’s technical assistance work. The aural evidence of UNESCO’s impact is located firmly within the prevailing sonic ideal: “clear and direct” and free from ‘noise.’50 This is particularly true relative to another soundscape which listeners (and particularly women) are presumed to be familiar with: the comparatively ‘noisy’ marketplace of modern Western consumerism. The use of that gendered trope speaks to the programme’s Western origin and the intended broadcast location––it seems to be particularly aimed at an Anglo-American public as the programme also only singles out costs-per-capita for the US and England.51 This is of course a far-cry from the global public imagined in the resolution establishing the UN’s Department of Public Information.52 This case evinces a particularly narrowly Western conception of the international public that is steeped in the programme’s cold war production context. Despite its lofty universalist aspirations, UNESCO Radio was reliant on domestic producers and broadcasters (this programme was aired in the US by the American Broadcasting Corporation),53 and was at this stage embedded within the geopolitical and ideological conditions of these local infrastructures.54

Further, the relatively quiet, studio-like, and acoustically controlled presentation of the broadcast’s ‘UNESCO-sounds’ meaningfully resonates with some of the depicted activities, such as spraying DDT to “ge[t] rid of malaria,”55 and the Arid Zone Program (which is framed elsewhere officially as a battle of “Men Against the Desert”).56 Here, “the power of human ingenuity over the physical environment”57 is signaled by sound and subject alike. This observable alignment between the contemporary ideals of sound-science and the world organization’s self-representation is intriguing in this small example, although it remains be seen how these aspects manifest across a multilingual archive spanning multiple decades. Research into the UN’s wider sound and audiovisual archive and related historical materials could reveal possible resonances (and dissonances) between the international organization’s sonic and diplomatic practices and its shifting ideals––and conceivably also help to recover evidence of how, where, and in what contexts all were heard.

Author Bio

Holden Carroll is a PhD candidate at the Amsterdam School of Historical Studies at the University of Amsterdam, having previously attained an MPhil in Politics and International Studies from the University of Cambridge. He researches novel approaches to our understanding of the international system and its history.

Notes

-

United Nations Secretary-General, Report to the General Assembly of the United Nations on The Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations, A-311-EN (1947), available from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/490632?ln=en, 32. ↩

-

Ibid., 32–3. ↩

-

For example, the eminent acoustics expert Leo Beranek was hired for the task of designing the system of “Altec loudspeakers” and “sound absorbing blankets” used throughout the United Nations General Assembly building. See description in Leo Beranek, Riding the Waves: A Life in Sound, Science, and Industry (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008): 110–1. ↩

-

I adopt this terminology as it has been employed by politics and international studies scholars to encapsulate the amalgamate relations of sound technologies and human bodies. Michelle D. Weitzel, “Audializing Migrant Bodies: Sound and Security at the Border,” Security Dialogue 49, no. 6 (2018), 427. A similar term, “sonic formation,” has also been employed in international relations work with the recent contribution of Xavier Guillaume and Kyle Grayson, “Sound Matters: How Sonic Formations Shape the Nuclear Deterrence and Non-Proliferation Regimes,” International Political Sociology 15 (2021): 153–71. ↩

-

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 31(I), Organization of the Secretariat A/RES/13(1) (February 13, 1946), available from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/209582, 15. ↩

-

Martin McMann, “Wiring the UN for World Listening,” Popular Science (September 1948): 122. Photographs by Hubert Luckett. Available here: https://books.google.nl/books?id=YCcDAAAAMBAJ. ↩

-

Examples include: Mahtab Shafiei and Kathryn Overton, “Peace is in the Air: Reducing Conflict Intensity With United Nations Peacekeeping Radio Broadcasts,” Conflict Management and Peace Science (forthcoming) (2023); Ali O. Nejadat and Mohammad N. Shatanawi, “The Role of United Nations’ Radio Stations in Promoting the Culture of Peace & Development in Developing Regions,” Sultan Qaboos University Journal of Arts & Social Science 5, no. 2 (2014); Anya Luscombe, “Eleanor Roosevelt, the United Nations and the Role of Radio Communications,” Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications 2, no. 1 (2016): 33–44. ↩

-

See for example the discussion in the resolution establishing UN Radio as a function of the organization’s Secretariat (note 6 above, at 15, 17): “The United Nations cannot achieve its purposes unless the peoples of the world are fully informed of its aims and activities…[t]he Department [of Public Information] should actively assist and encourage the use of radio broadcasting for the dissemination of information about the United Nations.” ↩

-

For an enlightening introduction to this subfield, see Mark M. Smith, “Producing Sense, Consuming Sense, Making Sense: Perils and Prospects for Sensory History” Journal of Social History 40, no. 4 (2007): 841–58. ↩

-

See note 5 above, and Jeremy E. Taylor and Russell P. Skelchy (eds.), Sonic Histories of Occupation: Experiencing Sound and Empire in a Global Context (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022); Damien Mahiet, Rebekah Ahrendt, and Frédéric Ramel, “Introduction: Diplomacy, Audible and Resonant,” Diplomatica 3, no. 2 (2021): 235–43 (and the other contributions to that special issue); Karin Bijsterveld, “Slicing Sound: Speaker Identification and Sonic Skills at the Stasi, 1966–1989” Isis 112, no. 2 (2021): 215–41; Ronald Michael Radano and Tejumola Olaniyan, Audible Empire: Music, Global Politics, Critique (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

-

Xavier Guillaume and Kyle Grayson, “Sound Matters: How Sonic Formations Shape the Nuclear Deterrence and Non-Proliferation Regimes,” International Political Sociology 15 (2021): 158, 159. Another similar term, “soundworld,” is employed in Damien Mahiet, Rebekah Ahrendt, and Frédéric Ramel, “Introduction, Diplomacy, Audible and Resonant,” Diplomatica 3 (2021): 238–9. ↩

-

“Close listening,” an archival practice advanced by Anette Hoffmann, is defined in her words by “the attempt to know by ear, that is, to grasp as much as possible of the audible features of a recording.” Anette Hoffmann, “Close Listening: Approaches to Research on Colonial Sound Archives” in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sonic Methodologies, edited by Michael Bull and Marcel Cobussen (New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021): 535. ↩

-

United Nations Audiovisual Library, “Easy as ABC - B is for Bargains,” accessed June 17, 2024, https://media.un.org/avlibrary/en/asset/d924/d924942. ↩

-

This alphabetical theme also plays on the fact it was intended for broadcast on ABC Radio in the United States. See description in archival entry, note 14 above. ↩

-

UNESCO Video and Sound Collections, “Easy as ABC: B is for Bargains,” (1958), accessed June 17, 2024, https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-6264. ↩

-

United Nations Audiovisual Library, “Easy as ABC - B is for Bargains,” broadcast April 27, 1959, accessed June 17, 2024, https://media.un.org/avlibrary/en/asset/d924/d924942. ↩

-

UNESDOC Digital Library, “Easy as ABC: programme B: Bargains,” MCR/3048, WS/048.6 (1958), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371497?posInSet=1&queryId=d37d768f-a130-47dc-a237-5c52c78b94b2, 11, 12. ↩

-

Phrasing cited from a 1949 Extraordinary Session document that outlines the goals and draft resolutions for UNESCO’s technical assistance program: UNESDOC, Technical Assistance for Economic Development,” 16 EX/2 (1949), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000161633. ↩

-

Ibid., 10, 12, 13. ↩

-

Diana K. Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016): 147. ↩

-

Ibid., 145. ↩

-

Ibid., 8. ↩

-

Ibid., 9. ↩

-

Ibid., 8, 9. While the narration refers to “a city in Italy,” the script specifies “ROMA.” ↩

-

UN AV Library, “Easy.” (link in note 18). ↩

-

UN Secretary-General, (see note 1, at 33). ↩

-

R. Murray Schafer, Our Sonic Environment and the Soundscape: The Tuning of the World (Rochester VT: Destiny Books, 1994): 43. ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 8. ↩

-

Ibid., 8–9. ↩

-

Ibid., 9. ↩

-

There are intriguing dynamics concerning the radio listener’s active imagination. See Jonathan Sterne “Sonic Imaginations,” in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Sterne (London and New York: Routledge, 2012): 5–6. See also Richard J. Hand and Mary Traynor, The Radio Drama Handbook: Audio Drama in Practice and Context (London: Bloomsbury, 2011): 4. ↩

-

See Reinhold Niebuhr, “The Theory and Practice of UNESCO,” International Organization 4, no. 1 (Feb. 1950): 3. Niebuhr cites early charges against UNESCO, including the “[US] Assistant Secretary of State George V. Allen[‘s notion] that the organization ‘had a wider public support’ and yet was ‘more widely criticized’ than any other international agency.” Allen attributed this rife criticism to the extent to which “UNESCO propaganda claims” tended to overstate the organization’s potential. ↩

-

Transcription and emphasis mine, from UN AV Library, “Easy,” starting at 14:08 (link in note 19). It is worth noting that this section on the Arid Zone Program appears to have been inserted after the script was written. Further, the version of the programme archived at the UNESCO Video and Sound Collections does not have this section, suggesting that there were at least two different versions of this American broadcast of the episode. ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 10. ↩

-

For a thorough discussion on the history of the association of noise and its associative meanings in relation to industrial technology, see Karin Bijsterveld, Mechanical Sound: Technology, Culture, and Public Problems of Noise in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008). ↩

-

Schafer, “Tuning,” at 43, 71. ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 16. Also notably here, there is a sound direction to apply an echo effect (“EKO” in the script’s shorthand), though this appears to not have been used to a noticeable effect in the final mix. ↩

-

Christian J. Steinmetz and Joshua D. Reiss, “pyloudnorm: A Simple Yet Flexible Loudness Meter in Python,” Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London (2018), 1–8, https://csteinmetz1.github.io/pyloudnorm-eval/paper/pyloudnorm_preprint.pdf. The GitHub page for the project is https://github.com/csteinmetz1/pyloudnorm. ↩

-

Ibid., 2. ↩

-

International Telecommunication Union, “Algorithms to Measure Audio Programme Loudness and True-peak Audio Level” Recommendation ITU-R BS.1770-5 (11/2023), accessed June 17, 2024, https://www.itu.int/dms_pubrec/itu-r/rec/bs/R-REC-BS.1770-5-202311-I!!PDF-E.pdf. ↩

-

See Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America 1900–1930 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 171–72. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The UNESCO Courier, “Noise Pollution” (July 1967), available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000078367/PDF/078367engo.pdf.multi. ↩

-

Thompson, Soundscape, 171. ↩

-

UN Secretary-General, Report, 33. ↩

-

Thompson, Soundscape, 171–2. ↩

-

Jens Steffek, International Organization as Technocratic Utopia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021): 12 ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 13. ↩

-

Thompson, Soundscape, 171. ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 16. ↩

-

UN General Assembly, (see note 6). ↩

-

It is worth noting that the Soviet Union had only joined UNESCO in 1954, four years before this recording was produced and eight years after UNESCO and UN Radio were founded. For a comprehensive survey of the USSR’s involvement with UNESCO, see Louis Howard Porter, Reds in Blue: UNESCO, World Governance, and the Soviet Internationalist Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023). ↩

-

UNESDOC, “Easy,” 10. ↩

-

Davis, Arid, 149. ↩

-

Thompson, Soundscape, 171–2. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: